I started this blog with a working title of ‘Diving into lichen’ but, on reflection, I realised this was a wildly inappropriate oversimplification. I’ve barely dipped my toe into the lichen shallows. And, if we’re to extend that metaphor a little further, it’s just enough to know that those shallows have dangerous rip-tides and fall away, precipitously, like a continental shelf-edge mere feet from the certainty of dry land.

Does this make lichen sound daunting? Well, they are… but at the same time, what a beautiful challenge they represent. Some years ago, aware that my Shetland home was festooned with lichen, from the shaggy greybeards that sprouted from old drystone walls, to the saffron crusts that smothered clifftop rocks and, tenaciously, the very roof of my old croft house, I did what I always do when I want to learn more about something – I bought a book.

If I’m honest, Shetland Lichens set me back a few pounds from the Shetland Times Bookshop, but also set my lichen-hunting back by a few years. I’d hoped for a field-guide that would help me to readily identify whatever I happened to find. What I got was a comprehensive monograph listing the lichens that had been found to date throughout Shetland, but with precious little information about how to set about actually identifying anything.

Life then got in the way of further progress. Researching and writing Orchid Summer ate into what precious little free time I had available to me. Then the cycle repeated itself with The Glitter in the Green… (Due to be published this year in the USA in April, and in the UK in June). Nonetheless, this past January, with lockdown keeping me at home, and spoilt by an uncharacteristically fine and prolonged spell of weather for Shetland at this time of year, I determined to try to get to grips with the lichens I could find close to home.

And this time I was, if not fully prepared, then certainly a little more confident than hitherto. I’d found Frank Dobson’s brilliant Lichens – An Illustrated Guide to the British and Irish Species and, online, I’d found a helpful cadre of lichenologists on Twitter who kindly held my hand as I made my first baby steps and wild stabs in the dark identifying what I stumbling across on Whalsay’s shores, walls, moors and outbuildings. Two of them, Brian Eversham and Mark Powell, I owe particular thanks to for their patience and assistance. A new world, one that had been under my nose all these years, was opening up…

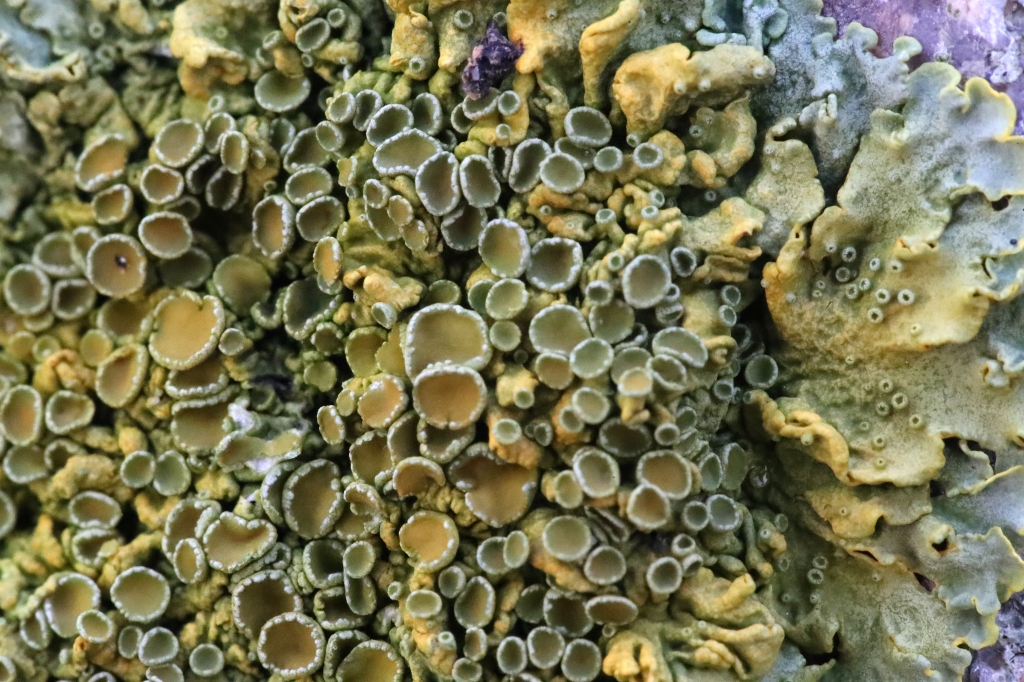

It all began with a couple of grey splats on the rocks at the shore – some with glistening black apoethecia (these are lichen fruiting bodies), and others with regular, sculptural disc-shaped apothecia, with neat rims around them like tiny jam tarts. These weren’t too hard to identify for myself – Tephromela atra and Ochrolechia parella respectively, both common lichens in these coastal parts.

A walk on the hill behind the house uncovered more unusual treasures – Sphaerophorus fragilis with delicate branches of filigree the colour of old ivory, and my first Cladonia species – the red matchsticks of Cladonia floerkeana and C. bellidiflora, and the green pixie cups of what may, or may not, be C. chlorophaea – the latter are needing further investigation. This, I was finding, is part of the joy of lichen-hunting – solving some identities isn’t straightforward, but nor should that be off-putting – it’s like solving a knotty riddle or crossword puzzle clue. There’s some satisfaction in a hard-earned resolution.

Nearby were some foliose lichens amongst the moss that blankets much of the hill – the wrinkled and somehow ancient ‘leaves’ of Peltigera membranacea, and the smoother, chestnut-apothecia bearing P. hymenina. The latter seems to be previously unrecorded on Whalsay – as were several more of the lichens I was finding. In the kirkyard were Whalsay’s first records of Physcia tenella, a fabulous grey lichen with corrugated, exuberant black apothecia, and the gorse-yellow branches of Xanthoria candelaria.

Another Xanthoria, X. parietina, covers rocks at the shore in a rich mustard crust. On the shaded walls of an old stone sheep dip I found it growing in more glaucous tones. Those sheep dips also yielded the gorgeous, subtle Caloplaca crenularia – a grey lichen with conker-coloured apothecia, easily overlooked but, on closer examination, a stunner.

Other Caloplaca lichens were more obvious – the yellow species found on the shore were unmissable, particularly the black and orange C. microthallina and deep orange C. marina. Amongst them was a prize – not a particularly rare lichen, but one that’s surely overlooked in Shetland – C. maritima, a lichen of lemon and lime tones that’s hitherto only recorded from Fair Isle.

Some of these lichens have English names but, while I’m usually a great fan of colourful and evocative language like that found amongst the English species names of moths and hummingbirds, in the case of lichens I’m sticking to the scientific names. That’s because the world of lichen has a language all of its own – a lichen lexicon. From apothecia to Zwackhiomyces (the latter a fungus found on Xanthoria parietina), I’m loving diving into a sea of new words.

I’ve come to realise that lichens are everywhere here – and that there are a wealth of discoveries to be made that help to add to our understanding of their distribution here in the islands. It’s like the scales have fallen from my eyes in the first few weeks of this year, and I can’t wait to see what else I can find. There’s an entirely new world out there on my doorstep waiting to be explored, and my voyage of discovery is only just beginning.

A few years ago, I set out to find Pugsley’s Marsh Orchids in Shetland. They’d never been recorded here before, but it seemed there was a reasonable chance they had, at least once upon a time, occurred here given their range extends up the west side of Ireland and Scotland. I looked for suitable habitat and, after a few sites had drawn a blank, I hit the jackpot – a small colony of Pugsley’s Marsh Orchids in a fenced off flush in the corner of an otherwise unremarkable grassy field.

A few years ago, I set out to find Pugsley’s Marsh Orchids in Shetland. They’d never been recorded here before, but it seemed there was a reasonable chance they had, at least once upon a time, occurred here given their range extends up the west side of Ireland and Scotland. I looked for suitable habitat and, after a few sites had drawn a blank, I hit the jackpot – a small colony of Pugsley’s Marsh Orchids in a fenced off flush in the corner of an otherwise unremarkable grassy field. Of course, it’s not always that simple… usually, one can’t just decide to go and look for something in a place it’s never been seen before and have any hope of actually finding it. Just sometimes, though, it does work… and yesterday, the planets aligned and it happened again.

Of course, it’s not always that simple… usually, one can’t just decide to go and look for something in a place it’s never been seen before and have any hope of actually finding it. Just sometimes, though, it does work… and yesterday, the planets aligned and it happened again. Five minutes later, I found my first flowering plant and, around it, many more flowering and non-flowering examples. Once I got my eye in, I kept seeing more and more plants. Slowly and carefully walking a 10 metre transect, I counted 250 plants. To put that in perspective, Lesser Twayblade is known from just a handful of sites in Shetland, and I’ve never found more than 40 plants at the best site I know on Unst. I ran home for my camera and, on returning, promptly found another patch of 50 more plants, including a dozen growing side by side in one small mossy area. Can you see them all?

Five minutes later, I found my first flowering plant and, around it, many more flowering and non-flowering examples. Once I got my eye in, I kept seeing more and more plants. Slowly and carefully walking a 10 metre transect, I counted 250 plants. To put that in perspective, Lesser Twayblade is known from just a handful of sites in Shetland, and I’ve never found more than 40 plants at the best site I know on Unst. I ran home for my camera and, on returning, promptly found another patch of 50 more plants, including a dozen growing side by side in one small mossy area. Can you see them all? They’re undoubtedly overlooked throughout Shetland – they’re tiny, barely two centimetres tall, and I’m sure my newly found colony will number many more than the 300 plants I counted in the space of an hour.

They’re undoubtedly overlooked throughout Shetland – they’re tiny, barely two centimetres tall, and I’m sure my newly found colony will number many more than the 300 plants I counted in the space of an hour. It’s not exactly a secret that I’m busy researching and writing a new book – something on a larger, grander and more sparkly scale than

It’s not exactly a secret that I’m busy researching and writing a new book – something on a larger, grander and more sparkly scale than  Those birds came to mind recently when I was in Cuba spending time looking for Bee Hummingbirds. I spent a while exploring the Zapata peninsula and there I found myself face to face with pigeons quite unlike any back home in Europe – although, as an aside,

Those birds came to mind recently when I was in Cuba spending time looking for Bee Hummingbirds. I spent a while exploring the Zapata peninsula and there I found myself face to face with pigeons quite unlike any back home in Europe – although, as an aside,  Blue-headed Quail-doves make up most of the feeding party – nine bold birds walked around me, right up to and then even between my feet, too close most of the time to focus my camera upon their eponymous cobalt blue crowns. Shyer still, a grey form slipped out into the ride leading to the clearing in which I stood. A Grey-fronted Quail-dove, like a ghost on the edge of vision. It finally crept a little closer, revealing a rich violet saddle and back. Not such a shrinking violet after all.

Blue-headed Quail-doves make up most of the feeding party – nine bold birds walked around me, right up to and then even between my feet, too close most of the time to focus my camera upon their eponymous cobalt blue crowns. Shyer still, a grey form slipped out into the ride leading to the clearing in which I stood. A Grey-fronted Quail-dove, like a ghost on the edge of vision. It finally crept a little closer, revealing a rich violet saddle and back. Not such a shrinking violet after all. The day seemed to deliver more and more pigeons and doves – rich cinnamon Zenaida Doves haunted the forest margins, barrel-chested White-crowned Pigeons streamed overhead as the light bled from the sky in late afternoon, and of course, there were feral pigeons too – those selfsame descendants of Rock Doves that we know from British city centres are in Cuba too. My last bird of the day was altogether more special, though. Common Ground Dove is, as the name suggests, not the rarest of its tribe – but they’re tiny, compact doves of immense character, with delicate scaly plumage about their breasts and heads and an iridescence about their crown and nape that makes them look as if they’ve been dipped in opals.

The day seemed to deliver more and more pigeons and doves – rich cinnamon Zenaida Doves haunted the forest margins, barrel-chested White-crowned Pigeons streamed overhead as the light bled from the sky in late afternoon, and of course, there were feral pigeons too – those selfsame descendants of Rock Doves that we know from British city centres are in Cuba too. My last bird of the day was altogether more special, though. Common Ground Dove is, as the name suggests, not the rarest of its tribe – but they’re tiny, compact doves of immense character, with delicate scaly plumage about their breasts and heads and an iridescence about their crown and nape that makes them look as if they’ve been dipped in opals. My next blog post was meant to be all about a summer that’s been largely spent working with butterflies in France, Greece and Spain – a sun-drenched, joyous examination of a strand of my developing life as a wildlife tour leader alongside the nature writing irons I keep in the fire.

My next blog post was meant to be all about a summer that’s been largely spent working with butterflies in France, Greece and Spain – a sun-drenched, joyous examination of a strand of my developing life as a wildlife tour leader alongside the nature writing irons I keep in the fire. But who am I fooling? This hasn’t been that half-hearted a search. I’ve been scrambling up and down steep mountainsides clad in deep, mossy forest, and have pushed my way through overgrown thickets following the tracks carved in the understory by wild boar. Parts of rural France have the feeling of full-blooded wildwood.

But who am I fooling? This hasn’t been that half-hearted a search. I’ve been scrambling up and down steep mountainsides clad in deep, mossy forest, and have pushed my way through overgrown thickets following the tracks carved in the understory by wild boar. Parts of rural France have the feeling of full-blooded wildwood. Researching and writing the Ghost Orchid chapter of

Researching and writing the Ghost Orchid chapter of  Sad to say, I didn’t find a Ghost Orchid on this occasion. I am, perhaps, a week or two too late this summer for this area of France. What I did find was, on the one hand, promising – woodland floors thick with Dutchman’s Pipe Monotropa hypopitys and an abundance of fungal bodies that hints at a rich myccorhizal network beneath my feet – just the sort of place a Ghost Orchid might favour.

Sad to say, I didn’t find a Ghost Orchid on this occasion. I am, perhaps, a week or two too late this summer for this area of France. What I did find was, on the one hand, promising – woodland floors thick with Dutchman’s Pipe Monotropa hypopitys and an abundance of fungal bodies that hints at a rich myccorhizal network beneath my feet – just the sort of place a Ghost Orchid might favour. Spending so much time in dark, remote places provides time for the mind to explore darker recesses of one’s fears. It’s fashionable in contemporary nature writing to speak of woods in warm, affectionate tones, but that’s not always how they make us feel. Or, at least, not me. An eroded cross marks the path up into the trees. Brown bones strewn on the dead leaves at one’s feet are an unsubtle clue to the cycles of life that have played out in times past, but give no hint of what end befell the animal that passed that way before me.

Spending so much time in dark, remote places provides time for the mind to explore darker recesses of one’s fears. It’s fashionable in contemporary nature writing to speak of woods in warm, affectionate tones, but that’s not always how they make us feel. Or, at least, not me. An eroded cross marks the path up into the trees. Brown bones strewn on the dead leaves at one’s feet are an unsubtle clue to the cycles of life that have played out in times past, but give no hint of what end befell the animal that passed that way before me. Those extravagant fungi are flourishing on decaying matter. And when low clouds sweep in and envelop the mountains, the birdsong suddenly stops, and all one can hear is the shocking report of a shot ringing out nearby, and the ringing bell-tones of a hunter’s dogs giving voice… then it is becomes hard to leave the dubious sanctuary of the trees and expose oneself to unseen eyes in open ground.

Those extravagant fungi are flourishing on decaying matter. And when low clouds sweep in and envelop the mountains, the birdsong suddenly stops, and all one can hear is the shocking report of a shot ringing out nearby, and the ringing bell-tones of a hunter’s dogs giving voice… then it is becomes hard to leave the dubious sanctuary of the trees and expose oneself to unseen eyes in open ground. I found myself torn by my time alone in the montane forests. Pulled by the irresistible urge to discover unseen gatherings of pallid, otherworldly orchids… and repelled by the fears with which my imagination painted the landscape.

I found myself torn by my time alone in the montane forests. Pulled by the irresistible urge to discover unseen gatherings of pallid, otherworldly orchids… and repelled by the fears with which my imagination painted the landscape.